As a small child growing up in Togo, Modupeola Fadugba was terrified of the sea; its seemingly limitless depths and lack of boundaries perturbed her. The swimming pools that she encountered upon moving to the United States at the age of five felt less threatening, but she did not fully overcome her fear of water until faced with compulsory lap-swimming classes at boarding school in England, aged eleven. Teetering on the edge of the pool, revelling in the spectacle she was creating for her classmates, eventually she had no choice but to jump in. Her single lap, completed in a drawn-out two or three minutes, taught her that despite her misgivings, swimming was something that she could, and would, conquer.

Fast-forward twenty years, and Fadugba found herself once again teetering on the edge of a pool, this time in Ibadan, Nigeria, where she was spending time with her family. She had just decided to commit herself full-time to art, and was feeling nervous and excited. Her brother was diving from the highest platform, and Fadugba climbed up next to him, only to find herself terrified once more of the water. Diving in seemed like an impossible feat, but with calm encouragement from her sibling, she took the plunge. Applause rang out around the pool; people shouted “Leap for Nigeria!”

Fadugba remembers these incidents with amusement, but also appreciation for their role in her artistic development. She cites the popular motto to “Do something every day that scares you” (sometimes attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt) as a guiding philosophy, alongside the rhetorical reassurance, “What’s the worst that could happen?”. Yet more than maxims applied straightforwardly to everyday life, for Fadugba these are points of departure in a broader exploration of fate. Risk, agency, and the play of chance through people’s lives occupy a central position in her artistic consciousness; swimming pools, with their moving human and aquatic bodies, are a natural environment in which to explore them.

Fadugba’s “pool” works fall broadly into two series of paintings, Tagged (2015–2016) and Synchronised Swimmers (ongoing). In Tagged, swimmers, mostly young black women, forge through water in pursuit of a red ball. Their hair is piled in braids on their bobbing heads, and their bodies for the most part lurk indistinctly in the depths of the pool. The water itself glistens with gold or silver leaf, creating an oily-looking surface patterned with eddies and ripples; these waters are beautiful and beguiling, but quite possibly dangerous. Titles such as “The Race”, “Reach”, “Women and Children, First”, and “Buy My Lot/Marry Me Next” reveal the pool as a place of competition and struggle. Many of the swimmers project determination mingled with desperation as they attempt to approach the red ball floating just out of reach.

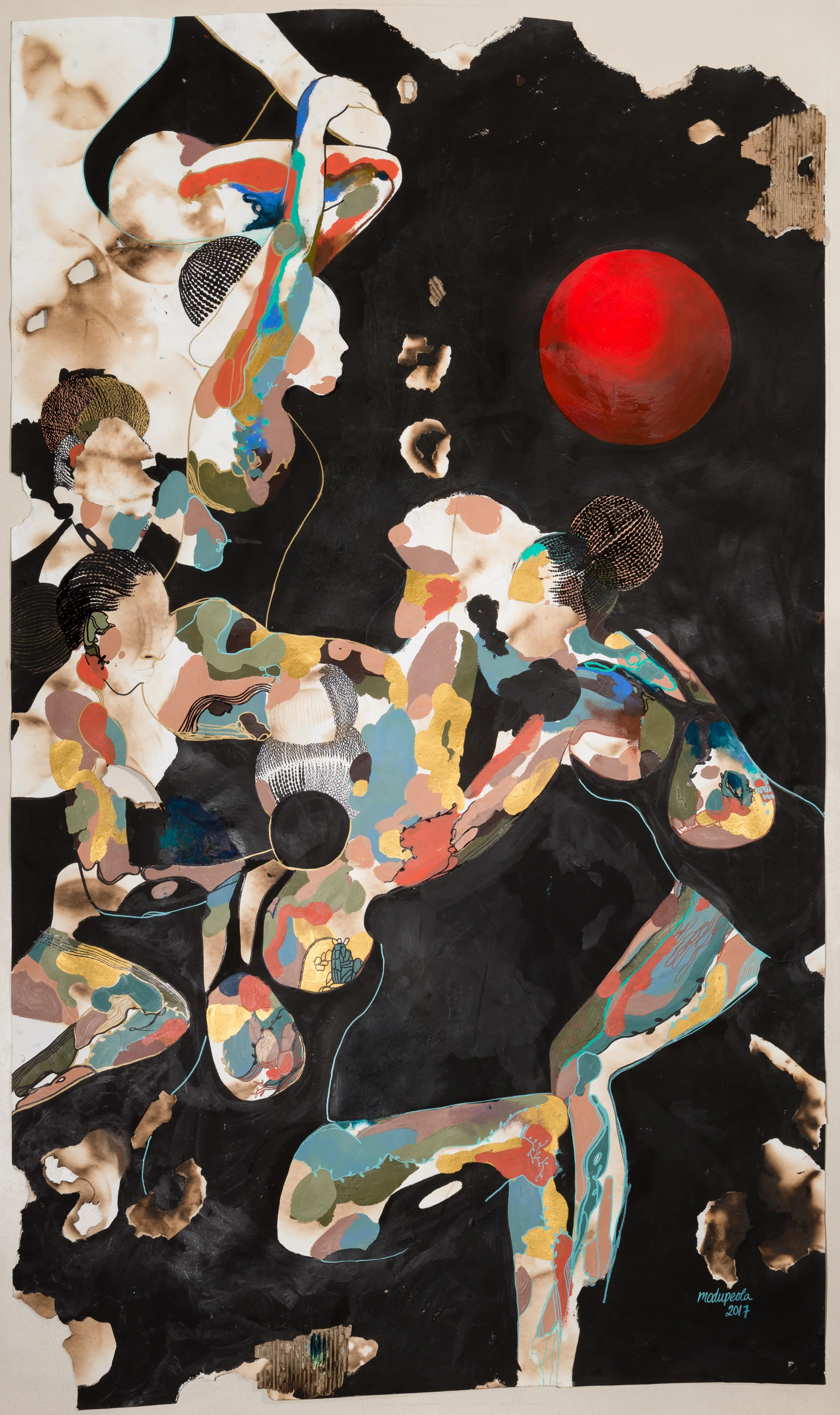

Synchronised Swimmers presents a different scenario, with Fadugba uniting her swimmers in a joint effort, their bodies clustering into living towers that uplift one of their number into the sky. In contrast to the figures in Tagged, these swimmers do not have defined features—rather, their faces are eerily blank—and identical hairstyles and sensible black bathing suits identify them as members of a sports team that finds its meaning in common purpose instead of individual achievement. Even this common purpose is a little ambiguous, however; the red ball still hovers enticingly, but the swimmers are not moving directly to capture it. The atmosphere is brighter, and the water seems comfortable instead of ominous. In “How to do a Double Platform Lift” (2016) it is abstracted into swathes of red and gold, while “How to Do a Platform Lift” (2016) takes place under the pool’s surface, with the shimmering water, painted in acrylic, oil, ink, and gold leaf, revealing patches of burnt paper underneath. A strange amalgam of water and fire (or its traces) comes together harmoniously, and the depths of the pool feel strangely calm.

Fadugba’s plunge off the diving board in Ibadan coincided with her plunge into the art world, and in her subsequent work the pool has become a metaphor for this arena that she regards with wary anticipation. Indeed, Fadugba’s practice has become a reflexive avenue for exploring and critiquing the art world, and the development in her work from Tagged to Synchronised Swimmers might be seen as a marker of her evolving understanding of the field and her place within in. As she has remarked, the pool, “not unlike the art world, represents luxury and risk simultaneously”. In the depths of the swirling water, Fadugba represents the profundities of meaning and emotion expressed through art, hinting at the power of artworks to submerge us, their flow encircling us and swaying our thoughts in one direction or another. At the same time, directly confronting the construction of value in the art market, she incorporates the red ball as a sign of the red dot used to indicate sales of artworks. This transactional assessment an artwork’s value, she suggests, is both an important method of validation and a trap. The swimmers in Tagged, like artists, attempt to navigate their way through this watery landscape, with one eye on the ball and the other on their competitors. Synchronised Swimmers, by contrast, begins to explore more collaborative ways of being in the water together.

Fadugba’s fondness for games weaves throughout her practice. In her writings accompanying Tagged, she stipulates only two rules for the game: stay in the pool, and (pretend to) ignore the red ball. Survival and success in the art world, she notes, depend not only on an artist’s ideas and skills, but also her stamina and adeptness at surreptitiously courting the market. Individual works in the series explore different perspectives on the game of art, but also develop parallels between the art world’s value system and unequal constructions and experiences of worth more generally. “Tagged: Senegalese Boys” (2015), in which five youths float in proximity to a red ball, is a meditation on the predicament of child divers near Gorée Island, off the coast of Dakar, Senegal, who swim to collect coins thrown to them by (mostly white) tourists. Since the coins are often foreign, and therefore worthless in the local economy, the game amounts to a treasure hunt with dubious rewards; and in the context of Gorée’s former role as a key slaving port, the interaction has disturbing echoes. Yet from her position in the tourist boat, marvelling at the boys’ agility, Fadugba wonders whether they are simply diving for the fun of it. Games, she reminds us, are universal; and despite wildly varied starting positions and (dis)advantages along the way, players often exercise a certain degree of autonomy over their own bodies.

A clue to Fadugba’s interest here is found in “How to do a Double Platform Lift”, with its palette of red and gold overlaid with sinuous black. The painting gives a nod to Chinese culture, in which the colours red and gold symbolise good fortune and wealth, and to Fadugba’s admiration for the precisely choreographed displays common at Chinese sporting events and festivals, where the individual performing body is subsumed within a collective mass acting in unison towards a common goal. Fadugba visited China in 2013, and returned to Nigeria inspired by the idea that Chinese-style discipline could enhance Nigerians’ efforts to tackle their own social issues. Her practice does not shy away from more didactic and activist modes, and while Synchronised Swimmers is not a direct call to action, it is a powerful proposition. Exactly what the red ball represents is left an open question, and the uncommon representation of a group of black women in a pool together adds another dimension to the work’s interpretation.

Dr. Evelyn Owen