the people's algorithm (2014 - 2017)

Growing up, my family placed an emphasis on educational fun, and I kept myself amused with self-made trivia games instead of the toys enjoyed by other children. A longing for toys and games, as well as a belief in the importance of education, have remained with me and have become integral to my practice. My practice has also been influenced by six years spent working in research, policy, and administration within Nigeria’s education sector.

In 2014, I created a game installation called The People’s Algorithm, which attempts to bring Nigeria’s enormous and complex education and unemployment crises into an accessible format. Ruled by chance and the roll of the dice, players move along a Monopoly-like board, learning facts and proffering solutions to some of the country’s most pressing educational challenges. The work creates a dynamic exchange of ideas between the audience, the artist, and the topic, seeking to activate constructive debate about how to change Nigeria’s education system for the better.

In chapter eight of Lewis Carroll’s Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Alice finds herself playing a game of croquet. Although familiar with the game, she soon discovers that in Wonderland the rules are somewhat unusual. Her ball is a curled-up hedgehog, which keeps running away; her mallet is an inverted, uncooperative flamingo; and the hoops are made of living playing cards, who refuse to stand still. Despite the unhelpful equipment and constantly moving targets, Alice bravely soldiers on, until play is brought to a halt by an unrelated dispute. Alice is invited to settle the matter, but prudently declines, and the game of croquet continues.

A game where the rules don’t make sense, where there are bizarre interruptions, where it seems impossible to win: this all makes some kind of sense in the topsy-turvy world of Wonderland. Children reading about Alice’s adventures may be forgiven for assuming that in real life one would never be given a hedgehog for a ball. But the unwelcome truth of Carroll’s story is that the world can sometimes be confusing, unpredictable, and unjust. Board games like Monopoly and The Game of Life invite players to strategize or assess risk, but the victor is often determined by the roll of the dice. We try to convince ourselves otherwise, but real life sometimes isn’t noticeably different.

What is needed, perhaps, is a tool kit for identifying the forces shaping life’s great game, for learning how to survive their tumultuous ups and downs, and for shaping them, wherever possible, in a positive direction. Modupeola Fadugba’s interactive game installation The People’s Algorithm (2014) rises to this challenge. For Fadugba, art is a platform for revealing and exploring the truths underpinning pervasive social structures and power dynamics. Yet her interest in examining human systems in all their beauty and fallibility is not simply descriptive; through her work, she seeks change, growth, and improvement.

The People’s Algorithm invites us to enter a childlike world of play and chance with a very serious motive: the game is a multifaceted intervention into Nigeria’s ongoing education and unemployment crisis. In 2013, the year before Fadugba made The People’s Algorithm, UNESCO reported that of around 60 million children worldwide being denied their right to basic education, 10.5 million were from Nigeria. Meanwhile, an average of only one in ten people applying to Nigerian universities are accepted, and even those leaving university with a degree may lack the skills and knowledge needed for success in the job market.

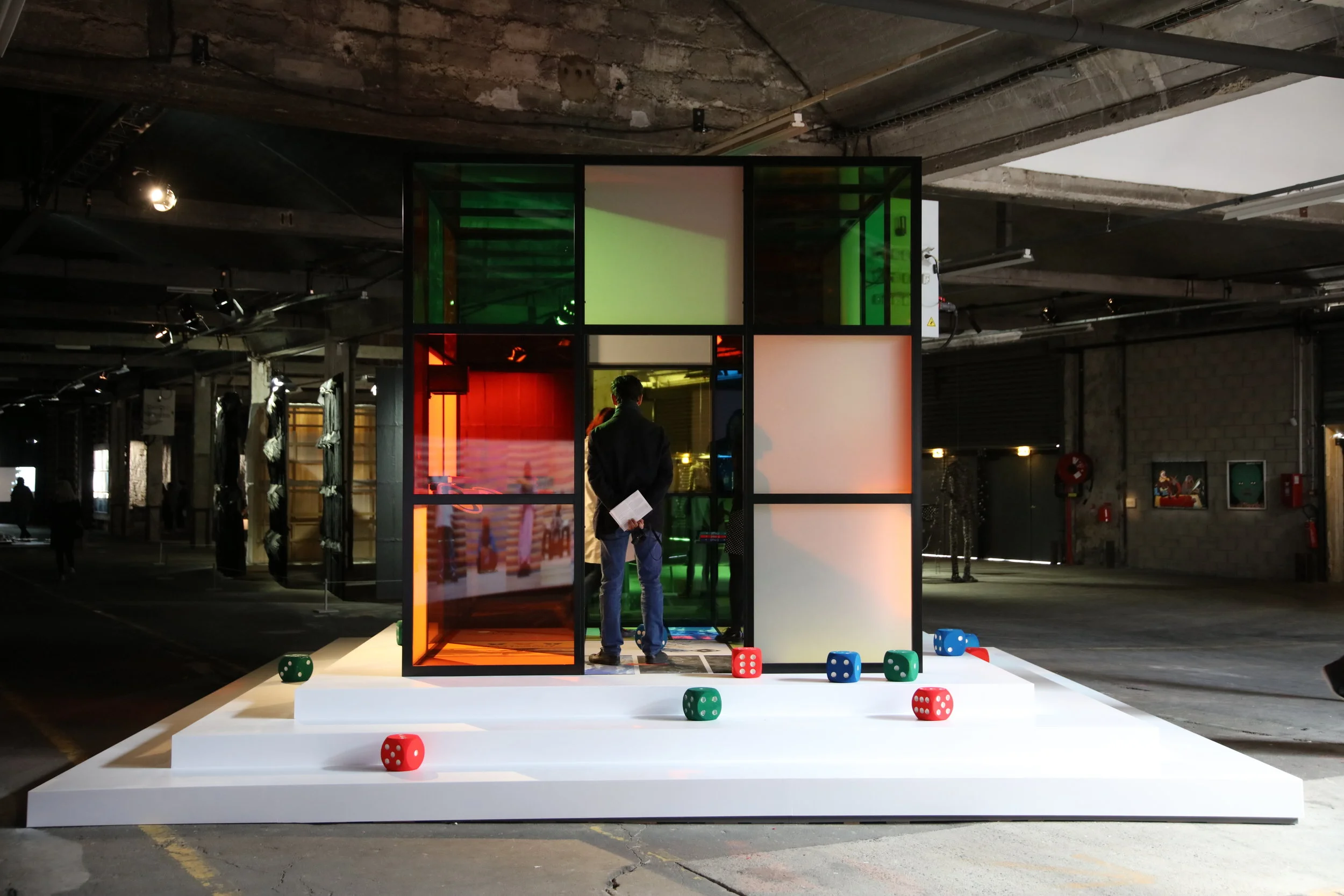

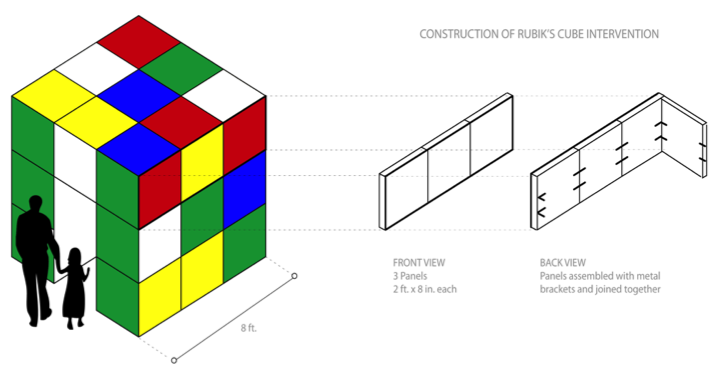

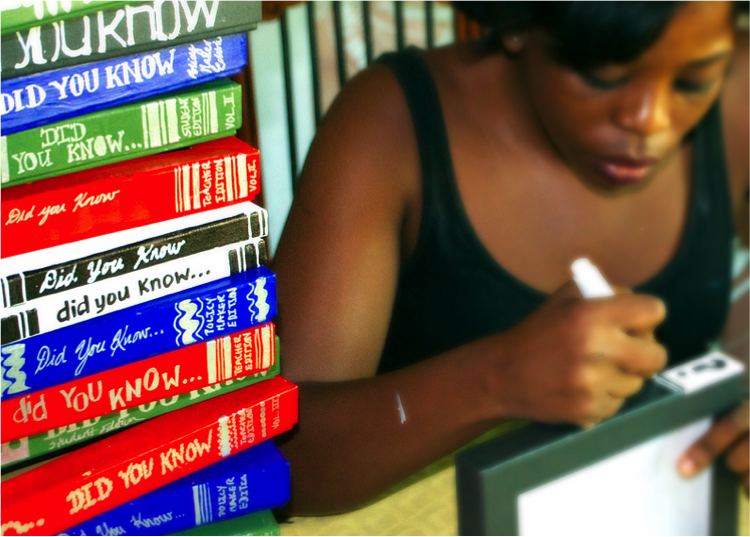

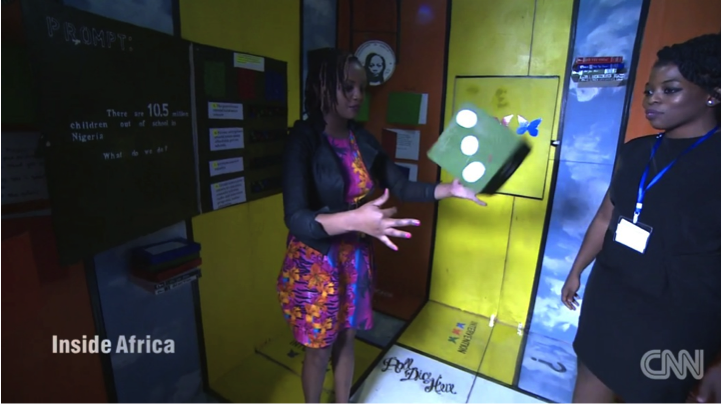

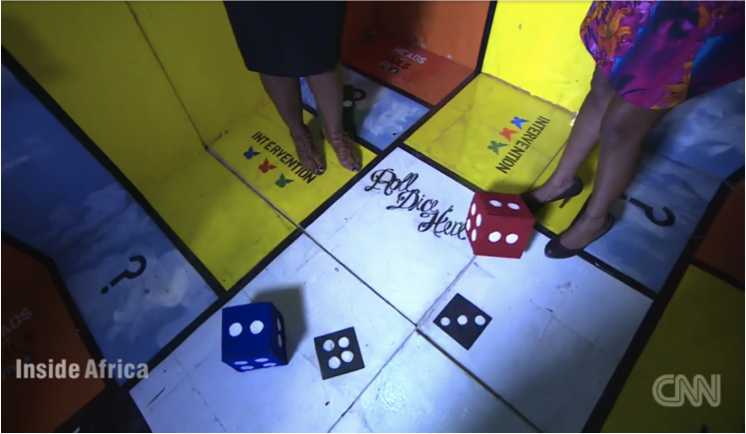

Fadugba has taken these statistics and experiences and condensed them into a plywood box measuring eight cubic feet, painted to resemble a giant Rubik’s Cube. The interior features a human-scale game board, a shelf holding books about education in Nigeria, and colourful foam dice. Fadugba is candid about her physically demanding and obsessive construction process, as well as her exhaustive research into game design, educational data, and young Nigerians’ personal stories. The incongruity between what looks at first glance like an oversized toy and the grave issues at stake is not coincidental. Play can be a useful strategy for demystifying complex issues, and is a tactic to draw her audience in. She explains: “It looks like child’s play. But you are actually gambling the fate of a nation.”

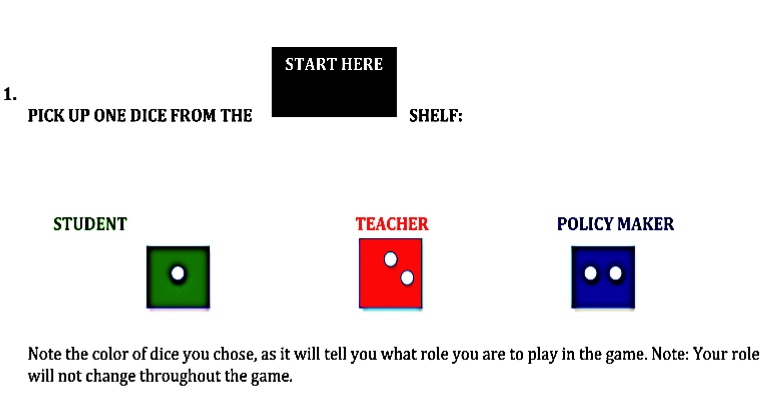

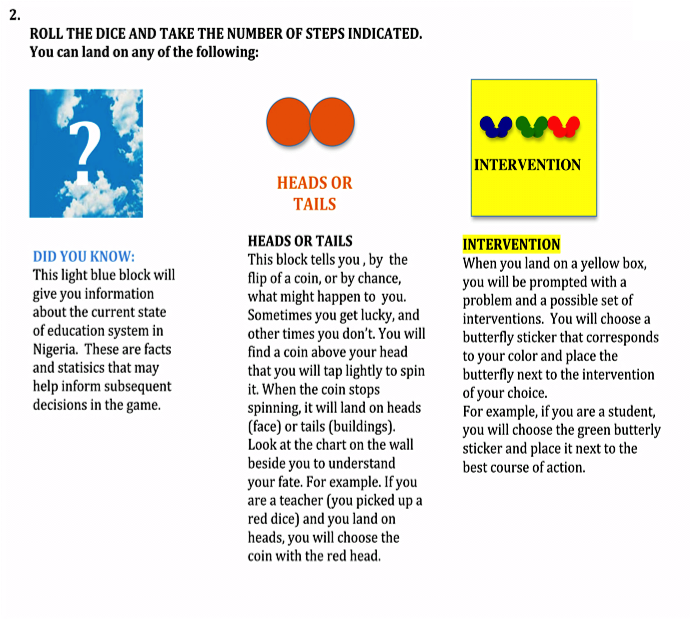

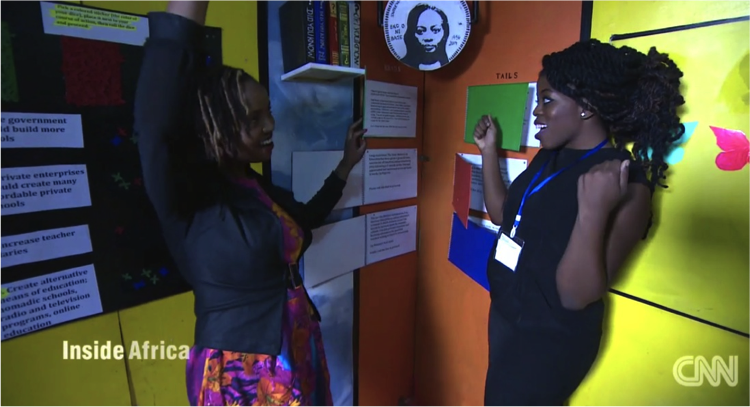

On stepping inside, players assume one of three roles: student, teacher, or policy maker. Depending on the roll of the dice, they may land on one of three blocks: “Did You Know?”, where they learn about the state of Nigeria’s education system; “Heads or Tails,” where they flip a larger-than-life coin to determine their fate; or “Interventions,” where they pick from a menu of possible solutions to problems.

Pathways through the game vary considerably, and are guided by the players’ choices but also by luck. Much like Alice and her hedgehog, a player may find herself handicapped by resources that are in some way lacking, or by circumstances beyond her control. On choosing the “student” role, she may find that school is suspended due to a spate of kidnappings in her district; as a “teacher,” she may be fortunate to receive an encouraging pay rise; as a “policy maker,” she may be unlucky enough to have to handle Ebola-related school closures. As the opportunities, challenges, lucky breaks, and frustrations mount up, the space inside the cube becomes a charged microcosm of the national predicament.

Fadugba was raised in a family where toys were scarce and fun was educational. Self-made trivia games and advanced mathematics papers were her main recourse for keeping out of trouble. These twin threads—a longing for toys and games, and a firm belief in the importance of education—have remained with her, and have been reinforced by six years spent working in research, policy, and administration within Nigeria’s education sector. Encounters with people occupying different positions in the education system alerted Fadugba to their competing needs and priorities, and to the ways in which they all participated in a structure that was by no means guaranteed to benefit them.

The People’s Algorithm is thus born out of both research and personal experience, and speaks to an urgent need for clarity and action. Yet something more animates Fadugba’s insistence on the role of art in this situation. She locates her practice within the realm of “patriotic worrying,” a Chinese intellectual tradition that emphasizes the moral obligation to solve national problems through deep reflection and the application of theory. Fadugba was born in Togo, and lived in several different countries as a child, but her patriotic worrying is directly firmly toward Nigeria, her home for much of her adult life. She is “asking us all to reimagine what can possibly be done, if we all play a role,” and her installation quite literally gives us each a part to play, even for just a few short minutes.

The title of the work, The People’s Algorithm, lays her ambitions bare. As a trained scientist with a degree in Chemical Engineering, Fadugba is at home with formulas and mathematical models. In the world of puzzles, the optimal sequence of actions to solve a given problem in the least number of steps is known as “God’s algorithm.” God, it is surmised, would always know the best next move. In turning this hypothetical algorithm over to “The People,” Fadugba makes a powerful statement about the potential within us all to alter the course of the future. Art, in this sense, becomes both a way to sound a “call to collective action” and a creative arena in which to learn and transform. There are no winners or losers in this game, only players, and above all, questions. In their asking and answering, we may find many small victories.

Dr. Evelyn Owen, March 2017